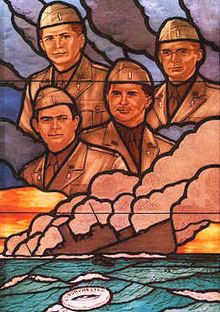

The Four Chaplains

This scene is a fairly accurate recreation of what actually happened. The eight members of the ship’s band, led by Wallace Hartley, did in fact play music in the first class lounge during the evacuation. Their last song played as they fell into the frigid North Atlantic was reported to be “Nearer, My God, to Thee” (and Hartley had told a friend he’d play that hymn if ever on a sinking ship). Whatever they played, it undoubtedly brought some peace to those in their final moments and some order to the chaos for those going to the lifeboats.

Today’s tale isn’t about these musicians. Today’s tale is about another group of men who were on a sinking ship and through the same stoicism and faith were able to help save lives. Today I’ll talk about the “Four Chaplains”.

I’m not a religious person at all, though I have taken to prayer in moments of hopelessness and do think there is some higher power. Even being agnostic at best, I found that the absolute best people were military chaplains. In my experiences they were calm, compassionate, and dutiful to a fault. They are always available for their “flock”, regardless if you’re a Jew and the Chaplain is a Methodist, they will provide services for you without fail and without complaint. Military chaplains really are a gift from God if you ask me.

There have been many chaplains awarded medals for bravery under fire, which is especially noteworthy as they are unarmed (at least since the Geneva Conventions took effect). In fact, nine chaplains have received the Medal of Honor: four during the Civil War, one in WWII, one in Korea, and three from Vietnam.

During WWII, four Army chaplains, commonly known as the “Four Chaplains”, received a special and unique honor among American awards and decorations.

- Reverend George Fox - A 42 year old Methodist minister from Pennsylvania. Already a veteran, he’d served during World War I as a 17 year old Army Ambulance Corpsman. He received the Silver Star, Purple Heart, and French Croix de Guerre for his bravery under fire in Europe. After the war he married, had two children (a boy and a girl), and became a minister. He entered service on August 8, 1942, the same day his son Wyatt enlisted with the Marines. Between the wars, he’d joined the American Legion and served as the Vermont American Legion’s state chaplain and historian.

- Rabbi Alexander Goode (PhD) - A 31 year old Jewish rabbi from Brooklyn, NY. The son of a rabbi, he first tried to become a Navy chaplain right after Pearl Harbor, but was rejected. He later tried with, and was accepted by, the Army. Goode was married to Theresa Flax, the daughter of a rabbi and niece to singer Al Jolson.

- Father John Washington - A 34 year old Roman Catholic priest. From New Jersey, after finishing seminary, he ministered at three parishes in New Jersey before enlisting.

- Reverend Clark Poling - A 32 year old, seventh generation evangelical minister ordained by the Reformed Church of America originally from Ohio. He graduated from Yale University’s Divinity School before working in Connecticut and New York. Rev Poling’s father, also a minister, had been a chaplain during WWI. Inspired by his father, when the Second World War broke out, Poling enlisted.

After receiving their training as Army chaplains, the four men were loaded with about 900 other men on the SS Dorchester, enroute to Greenland and ultimately Europe, leaving New York on January 23, 1943.

Dorchester was a converted merchant ship. Like many such vessels, it had minimal armor and armament and was a prime target for German U-boats. For safety, such ships would travel in a convoy. This convoy, SG-19, was comprised of three ships escorted by the US Coast Guard cutters, Tampa, Escanaba, and Comanche.

Life aboard ships such as Dorchester could be pretty miserable for the ground pounders being transited through the North Atlantic. Quarters were hot, cramped and dank. Worse still there was nothing to do for entertainment. A ship that during peacetime carried 314 passengers now carried nearly three times that many. The young men aboard ship thus had little to do but miss the comforts of home while coming to terms with the reality they were headed off to war.

The chaplains enlisted the help of the ship’s ranking NCO, First Sergeant MIchael Warish, to get the word out that they were organizing religious services for the men. They also organized a talent contest to serve as a distraction.

Entering a particularly dangerous area known as “Torpedo Junction”, the captain ordered all personnel aboard to sleep in their clothes and to wear life jackets at all times. The Army troops in the bowels of the ship often disregarded this order, either because the engine’s heat made them uncomfortable or because the life jackets were cumbersome and also uncomfortable.

The weather turned rough on February 2nd, causing the cancellation of the talent show. The Coast Guard had seen a U-boat on sonar, so they knew they were in dangerous waters. The weather cleared enough in the evening for the chaplains to organize an impromptu party in the main mess. Before bidding good night, the chaplains reminded the men of the captain’s order to wear their clothing (including boots and gloves) to bed with their life preservers.

On February 3rd, 1943 at 12:55am Dorchester was torpedoed by the German U-boat U-223 off Newfoundland. The torpedo took out the ship’s electrical, casting the whole ship into darkness. The troops, most of them below decks, started to panic.

The torpedo hit amidship, well below the water line. Dozens died in the initial explosion, the inrush of frigid water killed dozens more. Fully a third of the men who died did so in the first few moments of the torpedo attack.

Taking charge of the troops, the chaplains tried to bring order and calm to the men. Tending to the wounded and guiding the men out to the deck, they began passing out life jackets to the soldiers after finding a locker. The supply ran out before all the men had one. The Four Chaplains each took their own jackets off and passed them to the next troops in line. The chaplains then helped as many men onto lifeboats as they could.

One soldier recalled hearing a frantic scream of “I can’t find my life jacket,” over and over again. He heard a voice of calm say, “Here’s one, Soldier.” He saw Chaplain Fox take off his and give it to the man.

Private William B. Bednar, a survivor, said, “I could hear men crying, pleading, praying. I could also hear the chaplains preaching courage. Their voices were the only thing that kept me going.”

Rabbi Goode stopped Petty Officer John J. Mahoney from returning to his quarters. The young man explained to the chaplain that he’d forgotten his gloves. “Here take these,” he said, handing him the gloves off his hands. When the seaman said he couldn’t take his, the rabbi said, “Nevermind, I have two pair.” It was only in retrospect that Mahoney realized that Goode didn’t have two pairs, and had already resigned himself to his fate.

As the ship sank beneath the waves, with their mission complete, unable to save any more men or even themselves, the four men of God linked arms, prayed, and sang hymns in their final moments.

Grady Clark, a survivor of the wreck, said, “As I swam away from the ship, I looked back. The flares had lighted everything. The bow came up high and she slid under. The last thing I saw, the Four Chaplains were up there praying for the safety of the men. They had done everything they could. I did not see them again. They themselves did not have a chance without their life jackets.”

The survivors all told similar tales about one or more of the chaplains. They seemed to be everywhere on the deck of the stricken ship. Survivors reported hearing the chaplains, in their final moments, saying Jewish prayers in Hebrew and Catholic prayers in Latin in addition to English.

The ship sunk in only 27 minutes after the torpedo hit. Of the 904 men aboard that night, only 230 survived. Most that escaped the ship succumbed to the cold (water temperature was 34 °F and the air temperature was 36 °F). When additional rescue ships arrived, they described hundreds of bodies in the water, being kept at the surface by their life jackets.

Back home, before leaving, Chaplain Poling had asked his father (the minister and former military chaplain) to pray for him. “Not for my safe return, that wouldn't be fair. Just pray that I shall do my duty...never be a coward...and have the strength, courage and understanding of men. Just pray that I shall be adequate."

In 1960, Congress voted to authorize the President to posthumously honor the Four Chaplains with an appropriate medal. This became known as “The Four Chaplains Medal” or the “Chaplains Medal of Honor”. This is a distinct medal, only ever awarded to the Four Chaplains. Intended to be given the same weight and importance as the Medal of Honor, it was awarded because lobbying efforts to give these men the Medal of Honor required their actions to have been done during “combat with the enemy.”

Distinguished Service Cross

AWARDED FOR ACTIONS

DURING World War II

Service: Army

Rank: First Lieutenant

GENERAL ORDERS:

War Department, General Orders No. 93 (December 28, 1944)

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pride in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross (Posthumously) to [First Lieutenant (Chaplain) George L. Fox (ASN: 0-485690), First Lieutenant (Chaplain) John P. Washington (ASN: 0-463529), First Lieutenant (Chaplain) Alexander D. Goode (ASN: 0-485093), and First Lieutenant (Chaplain) Clark V. Poling (ASN: 0-477425)], United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an enemy of the United States. On the night of 3 February 1943, the U.S.A.T. Dorchester, a loaded troop transport, was torpedoed without warning by an enemy submarine in the North Atlantic and began to sink rapidly. In the resulting confusion and darkness some men found themselves without life jackets and others became helpless through fear and the dread of plunging into the freezing water. [Chaplains Fox, Washington, Goode, and Poling] moved about the deck, heroically and calmly, encouraging the men and assisting them to abandon ship. After the available supply of life jackets was exhausted they gave up their own and remained aboard ship and went down with it, offering words of encouragement and prayers to the last. [Chaplain Fox’s, Chaplain Washington’s, Chaplain Goode’s, and Chaplain Poling’s] great self-sacrifice, personal bravery and zealous devotion to duty exemplifies the highest traditions of the military forces of the United States and reflect great credit upon himself, the Chaplains Corps, and the United States Army.

Four Chaplains' Medal

Approved by an Act of Congress on July 14, 1960 (P.L. 86-656, 74 Stat. 521).

The statute reads as follows:

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the President is authorized to award posthumously appropriate medals and certificates to Chaplain George L. Fox of Gilman, Vermont; Chaplain Alexander D. Goode of Washington, District of Columbia; Chaplain Clark V. Poling of Schenectady, New York; and Chaplain John P. Washington of Arlington, New Jersey, in recognition of the extraordinary heroism displayed by them when they sacrificed their lives in the sinking of the troop transport Dorchester in the North Atlantic in 1943 by giving up their life preservers to other men aboard such transport. The medals and certificates authorized by this Act shall be in such form and of such design as shall be prescribed by the President, and shall be awarded to such representatives of the aforementioned chaplains as the President may designate.

Comments

Post a Comment