Ted Roosevelt - Medal of Honor for D-Day, June 6, 1944

As we commemorate the 75th anniversary of the largest amphibious assault in human history, I’d like to highlight one man amongst the 150,000+ there on June 6, 1944. Of the tens of thousands of Americans that fought on D-Day, 12 received Medals of Honor. Nine of those awards were made posthumously. The subject of my article is one of those posthumous awards.

Most people will have heard the name Theodore Roosevelt, I mean he is a legendary American historical figure. His face is one of only four on Mount Rushmore, and the only one from the 20th Century. He influenced American military and foreign policy all through today. He was a staunch conservationist and we have many national parks and the entirety of the US Forest Service due to him. He was also a true badass, surviving an assassin’s bullet to his chest, but not before giving a 50 page speech over the course of 90 minutes before seeking medical help. However, President Teddy Roosevelt’s contributions to today’s subject are purely paternal.

TR’s son, Theodore Roosevelt III (later Jr.), known as Ted, was an over the top character much like his father. Educated at Harvard, he was a successful banker and investor in his 20’s after college becoming quite wealthy. This would later aid him as he, like his father before him, stepped into the world of politics.

Before he could get political, world affairs drew his attention. Being a well off young man, and with a desire to prove himself in service to his country, he partook of the early reserve officer programs created in the 1910s. These programs, which are the forebearers of the ROTC program that came after the war, trained men in the basics of military leadership. Men who completed these programs, as Ted had done in 1915, became the backbone of the expanded US Army once the US entered the war.

The elder Theodore Roosevelt’s father had paid his way out of service during the Civil War, a stain on Teddy’s conscience, which is probably he worked so hard to prove his mettle during the Spanish-American War. He then instilled that sense of duty in his sons.

As the US entered the war, Teddy wired General “Black Jack” Pershing to inquire if his sons could accompany Pershing’s American Expeditionary Force as privates. Pershing accepted, but in light of their prior training, gave them commissions. Ted was commissioned a major, his younger brother Archie as a second lieutenant, while brother Quentin was already in the Army Air Service. The fourth Roosevelt son, Kermit, was serving with the British in present-day Iraq.

Ted volunteered for service in Europe the first chance he got. Made a battalion commander, he distinguished himself repeatedly. Brave and eager to take care of his men, he was unfazed by enemy fire and gas attacks and bought his men combat boots out of his own pocket. His division commander respected his leadership and he eventually rose to lieutenant colonel and command of the 26th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Division.

On May 28th, 1918, near Cantigny, France Ted and the 26th Regiment had just completed a raid. The then-major exposed himself to “intense machine-gun, rifle, and grenade fire” while he went forward to rescue and recover a wounded member of the raiding party. This is the battalion commander conducting daring rescues!

Later, on July 19, near Soissons, Major Roosevelt personally led companies of his battalion in an assault. Wounded by enemy fire in the knee, he refused to leave until he was physically carried from the field.

For these actions, Ted Roosevelt received the Distinguished Service Cross.

Gassed at Soissons in the summer of 1918, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for his “consistent gallantry, conspicuous energy, and marked efficiency in the operations around Cantigny, Soissons, and during the Meuse-Argonne offensive. By his devotion to duty, pronounced tactical ability, and brilliant qualities of leadership he contributed materially to the success of his regiment and of the 1st Division. He rendered services of signal worth to the Government in a position of great responsibility at a time of gravest importance.”

He also received two silver citation stars (which were later upgraded to Silver Stars when that award was created) during the course of the war. He was made a chevalier (knight) of the French Legion d’honneur.

After WWI, Ted was a key player in creating the organization that would become The American Legion. He was nominated the Legion’s first president but declined, not wanting to appear to be using the position solely for political gain.

Ted went into politics next. He held a wide variety of political positions, including Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Governor of Puerto Rico, and Governor-General of the Philippines. While working in these varied posts, he continued to maintain a reserve commission with the Army. He also took off on adventures with his brother Kermit, hunting the ovis poli (Marco Polo sheep) mountain goat in Kashmir and searching for, and finding, elusive wild pandas in China.

In 1940 he took a refresher course the Army was offering for reserve officers. As the US was preparing to enter the Second World War, he was promoted to colonel in The Army of the United States (the wartime national army). April 1941 he was put in command of his old regiment, the 26th Infantry, still with the 1st Infantry Division. Late in 1941 he was promoted to brigadier general.

Taking part in Operation Torch, the allied invasion of North Africa, Ted was known as a general who preferred the front lines over the command post. He frequently visited his troops and was exceedingly well liked by his men. In 1943 he was made assistant division commander of the 1st Infantry Division and was cited by the allied French with a croix de guerre for his gallantry under fire and the method in which he inspired the faith of his men.

Ted and his division commander, Major General Terry Allen, were of similar temperament. Their unorthodox leadership styles rankled their immediate boss, Lieutenant General George Patton, commander of 7th Army. Notoriously fickle, Patton did not like his officers to lack the “spit and polish” of professional soldiers. He did not like to see officers out of regulation uniforms, even when in the field for extended periods. He also had no difficulty in sending General Eisenhower, commander of American forces in the Mediterranean, derogatory reports on these officers. Ultimately, this led to Allen being removed from command of the 1st ID and Roosevelt’s reassignment as well.

In his journal, Patton described Roosevelt as “brave, but otherwise, no soldier” and, after his death, as “one of the bravest men I’ve ever known.”

Though he’d already fought through North Africa, Sicily, and onto mainland Italy, Roosevelt repeatedly asked for combat command. In the run up to the D-Day invasion, Ted was selected to serve as deputy commander of the 4th Infantry Division.

A man of action who wanted desperately to be at the front, he requested of his division commander to go ashore in the first wave. Of course this was denied. It is just not done. Colonels don’t go ashore with the first wave let alone generals. You don’t want to lose your most experienced officers in the early moments of a pivotal engagement.

Ted continued to press the idea. His contention was that in such a massive invasion as this (involving more than 150,000 troops) that a delay early in the engagement would have a ripple effect and cause chaos in later stages of the invasion. A novel approach, but one without much counter argument. He closed his justification by saying that he personally knew the officers and men of the lead elements and his presence among them would steady them.

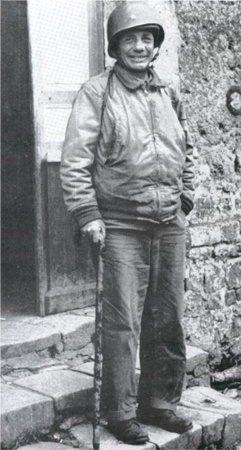

His commander found it hard to counter such a persuasive stance and so begrudgingly approved it, expecting Roosevelt to never survive. You see, by this point Roosevelt’s hard charging ways and his war injuries from years before had left him suffering a heart condition and crippling arthritis. He was forced to walk with a cane.

At 56, Roosevelt was the oldest man of the D-Day invasion, and landed in the first waves. He also has the distinction of being the only man to land at Normandy whose son also was part of the invasion. Roosevelt’s son, Captain Quentin Roosevelt II (named after Ted’s brother, who had died in action in the skies over Europe in the First World War), was also among the first wave of troops landed at Omaha Beach.

Brigadier General Ted Roosevelt was one of the first men to step off their landing craft at Utah Beach. Leading the 8th Infantry Regiment and the 70th Tank Battalion, Ted was informed they had landed a mile off course. Walking with his cane and carrying a pistol for his weapon, Ted personally conducted reconnaissance to find the causeways they were planning to use for the rest of the invasion. Connecting with his battalion commanders, Roosevelt decided they’d fight from their present location instead of trying to get into their assigned location, famously saying “We’ll start the war from right here!”

Imagine for a moment being a young private storming those beaches. More than 800 aircraft, 18,000 paratroopers, hundreds of ships launching rounds the size of a family sedan over your head, hundreds of landing craft, and tens of thousands of soldiers taking a heavily entrenched enemy. These young men had been told by their Supreme Allied Commander General Eisenhower just the day before that their “task will not be an easy one. [Their] enemy is well trained, well equipped and battle hardened. He will fight savagely.” As you approach the beach, your anxiety and apprehension threaten to boil over. Then on the beach you arrive and there’s a man old enough, or maybe older, than your father. He’s a general, and he’s cool, calm, and jovial. He’s telling jokes and anecdotes about his father the President to steady the men. He even recites poetry. For a young man who’d never seen combat, taking part in an invasion the likes of which had never been seen, and who knew that many of them would fall that day, the calm confidence of Ted was inspiring.

One soldier on the beach that day said that seeing the general walk around, seemingly unaware of enemy fire striking nearby, clods of dirt landing on his head, gave him the confidence to keep fighting. If the general is willing to do it, then so can the privates I suppose.

During the initial chaos of the invasion, in which nearly everyone was off their objective somehow, Roosevelt acted as a literal traffic cop. While under enemy fire he was directing troops to their new objectives using his cane and unsnarling traffic jams of trucks and tanks.

The division commander came ashore and was met by Roosevelt. Having said his goodbyes and never expecting to see the man again, he was a little emotional upon seeing him. However he quickly appreciated Roosevelt’s calm, calculated leadership as he was able to present his commander with a perfect picture of the tactical situation. Just as Ted had promised him he would do if allowed to go in first.

Through his ability to quickly and accurately assess the situation on the ground, he was able to redeploy his troops with such efficiency that they were able to take their objectives despite being out of position initially.

Years after the war, General Omar Bradley was asked what the bravest thing he’d ever seen in combat was. He replied simply, “Ted Roosevelt on Utah Beach.”

Ted’s physical difficulties and the heart condition he’d been able to keep secret from Army doctors caught up to him. On July 12, 1944, just a month after his incredible leadership on D-Day, he died of a heart attack at age 56. It was said of his father that “death had to take Roosevelt sleeping, for if he had been awake, there would have been a fight.” The German army had tried twice to kill Ted and was unsuccessful, but death came in the night.

On the day of his death he’d been chosen by Omar Bradley to command the 90th Infantry Division with the rank of Major General. When Eisenhower called the next morning to approve the orders, he was informed of Roosevelt’s passing.

Such familiar names to World War II buffs as Patton, Bradley, and Lawton Collins served as pallbearers at a secret battlefield funeral for Ted a few days after he died. He was initially buried in Sainte-Mère-Église. He was later reinterred in the American cemetery in Normandy. Ted’s brother Quentin, who was KIA during the First World War, was moved from his grave to rest alongside him.

For his bravery on June 6, 1944, Roosevelt was initially recommended for another Distinguished Service Cross, but this was upgraded by headquarters to the Medal of Honor. His award had been recommended before his death. He also received two more Silver Stars, both for actions in Tunisia, and a Legion of Merit.

CITATION:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Major (Infantry) Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. (ASN: 0-139726), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action serving with the 26th Infantry Regiment, 1st Division, A.E.F., near Cantigny, France, 28 May 1918. After the completion of a raid Major Roosevelt exposed himself to intense machine-gun, rifle, and grenade fire while he went forward and assisted in rescuing a wounded member of the raiding party. At Soissons, France, 19 July 1918, he personally led the assault companies of his battalion, and although wounded in the knee he refused to be evacuated until carried off the field.

CITATION:

The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pride in presenting the Medal of Honor (Posthumously) to Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. (ASN: 0-139726), United States Army, for gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty on 6 June 1944, while serving as a commander in the 4th Infantry Division in France. After two verbal requests to accompany the leading assault elements in the Normandy invasion had been denied, Brigadier General Roosevelt's written request for this mission was approved and he landed with the first wave of the forces assaulting the enemy-held beaches. He repeatedly led groups from the beach, over the seawall and established them inland. His valor, courage, and presence in the very front of the attack and his complete unconcern at being under heavy fire inspired the troops to heights of enthusiasm and self-sacrifice. Although the enemy had the beach under constant direct fire, Brigadier General Roosevelt moved from one locality to another, rallying men around him, directed and personally led them against the enemy. Under his seasoned, precise, calm, and unfaltering leadership, assault troops reduced beach strong points and rapidly moved inland with minimum casualties. He thus contributed substantially to the successful establishment of the beachhead in France.

Most people will have heard the name Theodore Roosevelt, I mean he is a legendary American historical figure. His face is one of only four on Mount Rushmore, and the only one from the 20th Century. He influenced American military and foreign policy all through today. He was a staunch conservationist and we have many national parks and the entirety of the US Forest Service due to him. He was also a true badass, surviving an assassin’s bullet to his chest, but not before giving a 50 page speech over the course of 90 minutes before seeking medical help. However, President Teddy Roosevelt’s contributions to today’s subject are purely paternal.

TR’s son, Theodore Roosevelt III (later Jr.), known as Ted, was an over the top character much like his father. Educated at Harvard, he was a successful banker and investor in his 20’s after college becoming quite wealthy. This would later aid him as he, like his father before him, stepped into the world of politics.

The elder Theodore Roosevelt’s father had paid his way out of service during the Civil War, a stain on Teddy’s conscience, which is probably he worked so hard to prove his mettle during the Spanish-American War. He then instilled that sense of duty in his sons.

As the US entered the war, Teddy wired General “Black Jack” Pershing to inquire if his sons could accompany Pershing’s American Expeditionary Force as privates. Pershing accepted, but in light of their prior training, gave them commissions. Ted was commissioned a major, his younger brother Archie as a second lieutenant, while brother Quentin was already in the Army Air Service. The fourth Roosevelt son, Kermit, was serving with the British in present-day Iraq.

Ted volunteered for service in Europe the first chance he got. Made a battalion commander, he distinguished himself repeatedly. Brave and eager to take care of his men, he was unfazed by enemy fire and gas attacks and bought his men combat boots out of his own pocket. His division commander respected his leadership and he eventually rose to lieutenant colonel and command of the 26th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Division.

On May 28th, 1918, near Cantigny, France Ted and the 26th Regiment had just completed a raid. The then-major exposed himself to “intense machine-gun, rifle, and grenade fire” while he went forward to rescue and recover a wounded member of the raiding party. This is the battalion commander conducting daring rescues!

Later, on July 19, near Soissons, Major Roosevelt personally led companies of his battalion in an assault. Wounded by enemy fire in the knee, he refused to leave until he was physically carried from the field.

For these actions, Ted Roosevelt received the Distinguished Service Cross.

Gassed at Soissons in the summer of 1918, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for his “consistent gallantry, conspicuous energy, and marked efficiency in the operations around Cantigny, Soissons, and during the Meuse-Argonne offensive. By his devotion to duty, pronounced tactical ability, and brilliant qualities of leadership he contributed materially to the success of his regiment and of the 1st Division. He rendered services of signal worth to the Government in a position of great responsibility at a time of gravest importance.”

He also received two silver citation stars (which were later upgraded to Silver Stars when that award was created) during the course of the war. He was made a chevalier (knight) of the French Legion d’honneur.

After WWI, Ted was a key player in creating the organization that would become The American Legion. He was nominated the Legion’s first president but declined, not wanting to appear to be using the position solely for political gain.

Ted went into politics next. He held a wide variety of political positions, including Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Governor of Puerto Rico, and Governor-General of the Philippines. While working in these varied posts, he continued to maintain a reserve commission with the Army. He also took off on adventures with his brother Kermit, hunting the ovis poli (Marco Polo sheep) mountain goat in Kashmir and searching for, and finding, elusive wild pandas in China.

In 1940 he took a refresher course the Army was offering for reserve officers. As the US was preparing to enter the Second World War, he was promoted to colonel in The Army of the United States (the wartime national army). April 1941 he was put in command of his old regiment, the 26th Infantry, still with the 1st Infantry Division. Late in 1941 he was promoted to brigadier general.

Taking part in Operation Torch, the allied invasion of North Africa, Ted was known as a general who preferred the front lines over the command post. He frequently visited his troops and was exceedingly well liked by his men. In 1943 he was made assistant division commander of the 1st Infantry Division and was cited by the allied French with a croix de guerre for his gallantry under fire and the method in which he inspired the faith of his men.

Ted and his division commander, Major General Terry Allen, were of similar temperament. Their unorthodox leadership styles rankled their immediate boss, Lieutenant General George Patton, commander of 7th Army. Notoriously fickle, Patton did not like his officers to lack the “spit and polish” of professional soldiers. He did not like to see officers out of regulation uniforms, even when in the field for extended periods. He also had no difficulty in sending General Eisenhower, commander of American forces in the Mediterranean, derogatory reports on these officers. Ultimately, this led to Allen being removed from command of the 1st ID and Roosevelt’s reassignment as well.

In his journal, Patton described Roosevelt as “brave, but otherwise, no soldier” and, after his death, as “one of the bravest men I’ve ever known.”

Though he’d already fought through North Africa, Sicily, and onto mainland Italy, Roosevelt repeatedly asked for combat command. In the run up to the D-Day invasion, Ted was selected to serve as deputy commander of the 4th Infantry Division.

A man of action who wanted desperately to be at the front, he requested of his division commander to go ashore in the first wave. Of course this was denied. It is just not done. Colonels don’t go ashore with the first wave let alone generals. You don’t want to lose your most experienced officers in the early moments of a pivotal engagement.

Ted continued to press the idea. His contention was that in such a massive invasion as this (involving more than 150,000 troops) that a delay early in the engagement would have a ripple effect and cause chaos in later stages of the invasion. A novel approach, but one without much counter argument. He closed his justification by saying that he personally knew the officers and men of the lead elements and his presence among them would steady them.

His commander found it hard to counter such a persuasive stance and so begrudgingly approved it, expecting Roosevelt to never survive. You see, by this point Roosevelt’s hard charging ways and his war injuries from years before had left him suffering a heart condition and crippling arthritis. He was forced to walk with a cane.

At 56, Roosevelt was the oldest man of the D-Day invasion, and landed in the first waves. He also has the distinction of being the only man to land at Normandy whose son also was part of the invasion. Roosevelt’s son, Captain Quentin Roosevelt II (named after Ted’s brother, who had died in action in the skies over Europe in the First World War), was also among the first wave of troops landed at Omaha Beach.

Brigadier General Ted Roosevelt was one of the first men to step off their landing craft at Utah Beach. Leading the 8th Infantry Regiment and the 70th Tank Battalion, Ted was informed they had landed a mile off course. Walking with his cane and carrying a pistol for his weapon, Ted personally conducted reconnaissance to find the causeways they were planning to use for the rest of the invasion. Connecting with his battalion commanders, Roosevelt decided they’d fight from their present location instead of trying to get into their assigned location, famously saying “We’ll start the war from right here!”

Imagine for a moment being a young private storming those beaches. More than 800 aircraft, 18,000 paratroopers, hundreds of ships launching rounds the size of a family sedan over your head, hundreds of landing craft, and tens of thousands of soldiers taking a heavily entrenched enemy. These young men had been told by their Supreme Allied Commander General Eisenhower just the day before that their “task will not be an easy one. [Their] enemy is well trained, well equipped and battle hardened. He will fight savagely.” As you approach the beach, your anxiety and apprehension threaten to boil over. Then on the beach you arrive and there’s a man old enough, or maybe older, than your father. He’s a general, and he’s cool, calm, and jovial. He’s telling jokes and anecdotes about his father the President to steady the men. He even recites poetry. For a young man who’d never seen combat, taking part in an invasion the likes of which had never been seen, and who knew that many of them would fall that day, the calm confidence of Ted was inspiring.

One soldier on the beach that day said that seeing the general walk around, seemingly unaware of enemy fire striking nearby, clods of dirt landing on his head, gave him the confidence to keep fighting. If the general is willing to do it, then so can the privates I suppose.

During the initial chaos of the invasion, in which nearly everyone was off their objective somehow, Roosevelt acted as a literal traffic cop. While under enemy fire he was directing troops to their new objectives using his cane and unsnarling traffic jams of trucks and tanks.

The division commander came ashore and was met by Roosevelt. Having said his goodbyes and never expecting to see the man again, he was a little emotional upon seeing him. However he quickly appreciated Roosevelt’s calm, calculated leadership as he was able to present his commander with a perfect picture of the tactical situation. Just as Ted had promised him he would do if allowed to go in first.

Through his ability to quickly and accurately assess the situation on the ground, he was able to redeploy his troops with such efficiency that they were able to take their objectives despite being out of position initially.

Years after the war, General Omar Bradley was asked what the bravest thing he’d ever seen in combat was. He replied simply, “Ted Roosevelt on Utah Beach.”

Ted’s physical difficulties and the heart condition he’d been able to keep secret from Army doctors caught up to him. On July 12, 1944, just a month after his incredible leadership on D-Day, he died of a heart attack at age 56. It was said of his father that “death had to take Roosevelt sleeping, for if he had been awake, there would have been a fight.” The German army had tried twice to kill Ted and was unsuccessful, but death came in the night.

On the day of his death he’d been chosen by Omar Bradley to command the 90th Infantry Division with the rank of Major General. When Eisenhower called the next morning to approve the orders, he was informed of Roosevelt’s passing.

Such familiar names to World War II buffs as Patton, Bradley, and Lawton Collins served as pallbearers at a secret battlefield funeral for Ted a few days after he died. He was initially buried in Sainte-Mère-Église. He was later reinterred in the American cemetery in Normandy. Ted’s brother Quentin, who was KIA during the First World War, was moved from his grave to rest alongside him.

For his bravery on June 6, 1944, Roosevelt was initially recommended for another Distinguished Service Cross, but this was upgraded by headquarters to the Medal of Honor. His award had been recommended before his death. He also received two more Silver Stars, both for actions in Tunisia, and a Legion of Merit.

Distinguished Service Cross

AWARDED FOR ACTIONS

DURING World War I

Service: Army

Rank: Major

Division: 1st Division, American Expeditionary Forces

GENERAL ORDERS:

War Department, General Orders No. 10 (1920)

CITATION:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Major (Infantry) Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. (ASN: 0-139726), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action serving with the 26th Infantry Regiment, 1st Division, A.E.F., near Cantigny, France, 28 May 1918. After the completion of a raid Major Roosevelt exposed himself to intense machine-gun, rifle, and grenade fire while he went forward and assisted in rescuing a wounded member of the raiding party. At Soissons, France, 19 July 1918, he personally led the assault companies of his battalion, and although wounded in the knee he refused to be evacuated until carried off the field.

Medal of Honor

AWARDED FOR ACTIONS

DURING World War II

Service: Army

Division: 4th Infantry Division

GENERAL ORDERS:

War Department, General Orders No. 77, September 28, 1944

CITATION:

The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pride in presenting the Medal of Honor (Posthumously) to Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. (ASN: 0-139726), United States Army, for gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty on 6 June 1944, while serving as a commander in the 4th Infantry Division in France. After two verbal requests to accompany the leading assault elements in the Normandy invasion had been denied, Brigadier General Roosevelt's written request for this mission was approved and he landed with the first wave of the forces assaulting the enemy-held beaches. He repeatedly led groups from the beach, over the seawall and established them inland. His valor, courage, and presence in the very front of the attack and his complete unconcern at being under heavy fire inspired the troops to heights of enthusiasm and self-sacrifice. Although the enemy had the beach under constant direct fire, Brigadier General Roosevelt moved from one locality to another, rallying men around him, directed and personally led them against the enemy. Under his seasoned, precise, calm, and unfaltering leadership, assault troops reduced beach strong points and rapidly moved inland with minimum casualties. He thus contributed substantially to the successful establishment of the beachhead in France.

Comments

Post a Comment